Can a sandwich save the day?

Sadly, not many niche sports cars are left now. Spiralling labour and material costs have turned what once were affordable cars into expensive toys for the few.

But a new technique could literally halve production costs and it’s fast too.

Furthermore, it is particularly applicable to electric cars, but let’s look at the traditional side first.

Usually, body panels are fixed onto complex wooden or steel-tubular frames along with lots of hammering and welding and many expensive man hours.

Intrinsically these techniques are very good. Wooden frames (Morgan, Marcos) can be surprisingly strong. The largely wooden WW2 Mosquito flew with a massive Merlin engine on each wing and you can’t get much more demanding than that.

Space frames are almost universal (Caterham, TVR, Westfield, Donkervoort, Maserati etc) and with body panels attached they are remarkably strong and light – if only we could get away from the labour-intensive procedures involved.

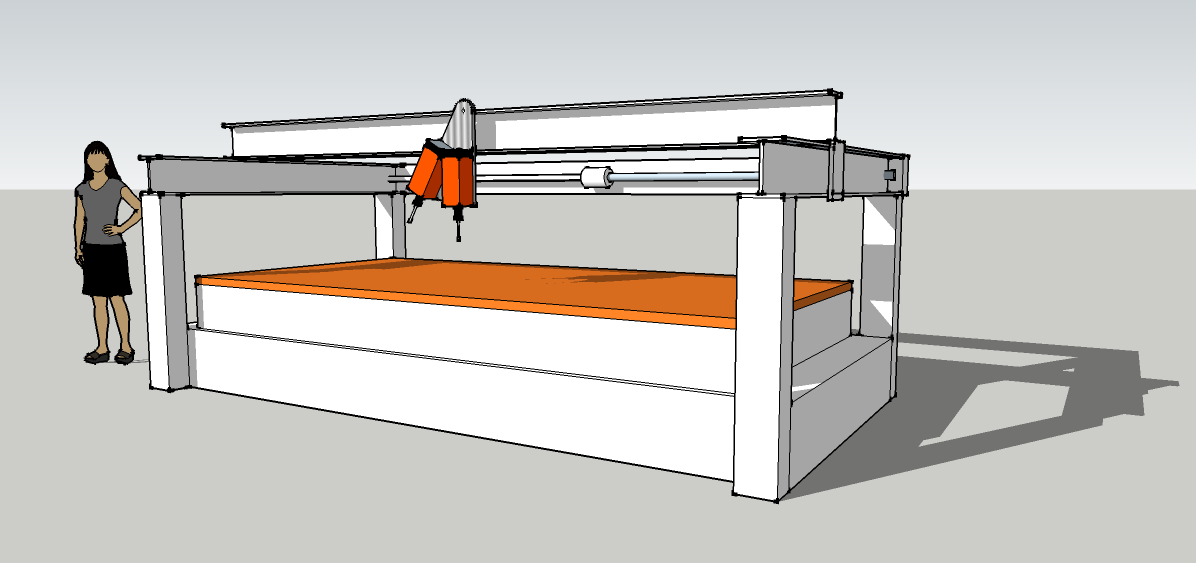

As it happens, we can combine complex wood and metal frames with attached body panels quite easily. Furthermore, it can be done with great speed and accuracy and all automated too.

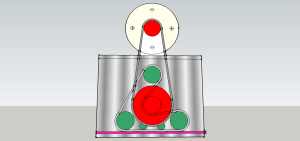

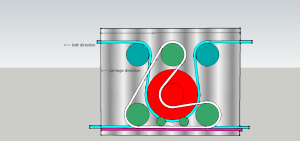

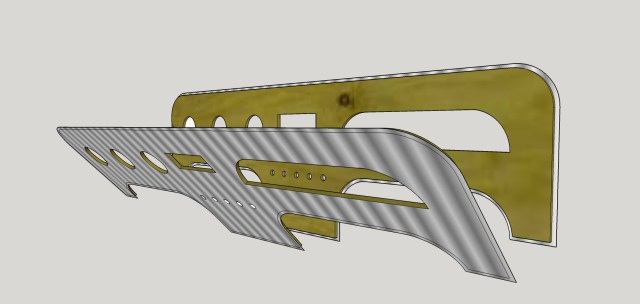

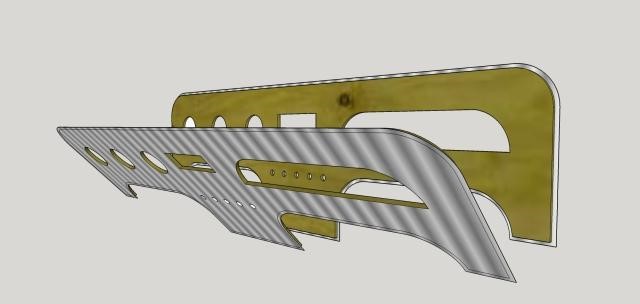

It all starts with a sandwich. A sheet of aircraft-grade birch plywood and an aluminium sheet glued together.

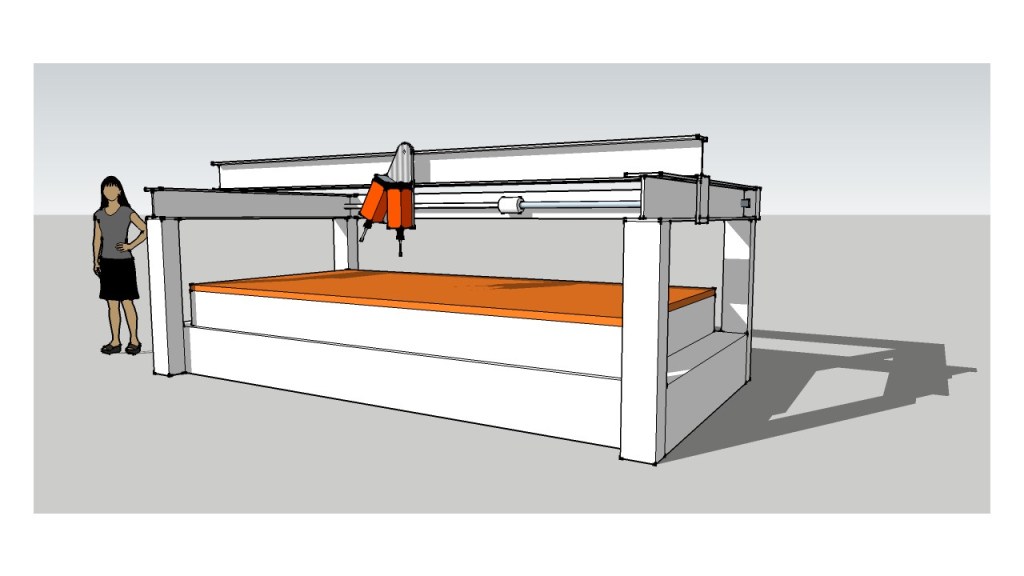

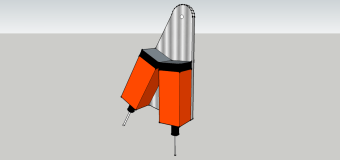

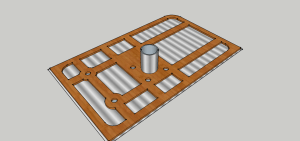

With a CNC router, machine away the plywood to leave complex shapes and struts to give strong, light and complex components. Any mounting holes or slots are accurately placed in seconds. Note how the aluminium body panels are already glued to the formed struts.

Next, a CNC laser cutter swiftly cuts through the aluminium sheet to separate the various components; deliberately exposed flanges can be peened over to increase strength and appearance.

Note that, at this stage, all the teams of tappers and welders have been replaced by a couple of CNC machines. Often the machines are beavering away with no one there at all – might as well turn the lights out then.

So far so good but this technique can be taken so much further.

Back-to-back panels

Panels can be doubled up with wood sandwiched in the middle and aluminium outsides. Immensely strong components are the result and with attractive curved edges if required. For example, a side body panel now strong enough to double as a chassis.

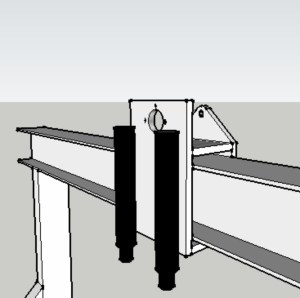

To enable through-bolts to be tightened without crushing the wood there will be plug pairs inside with a star washer in between to further transmit any applied load into the wood.

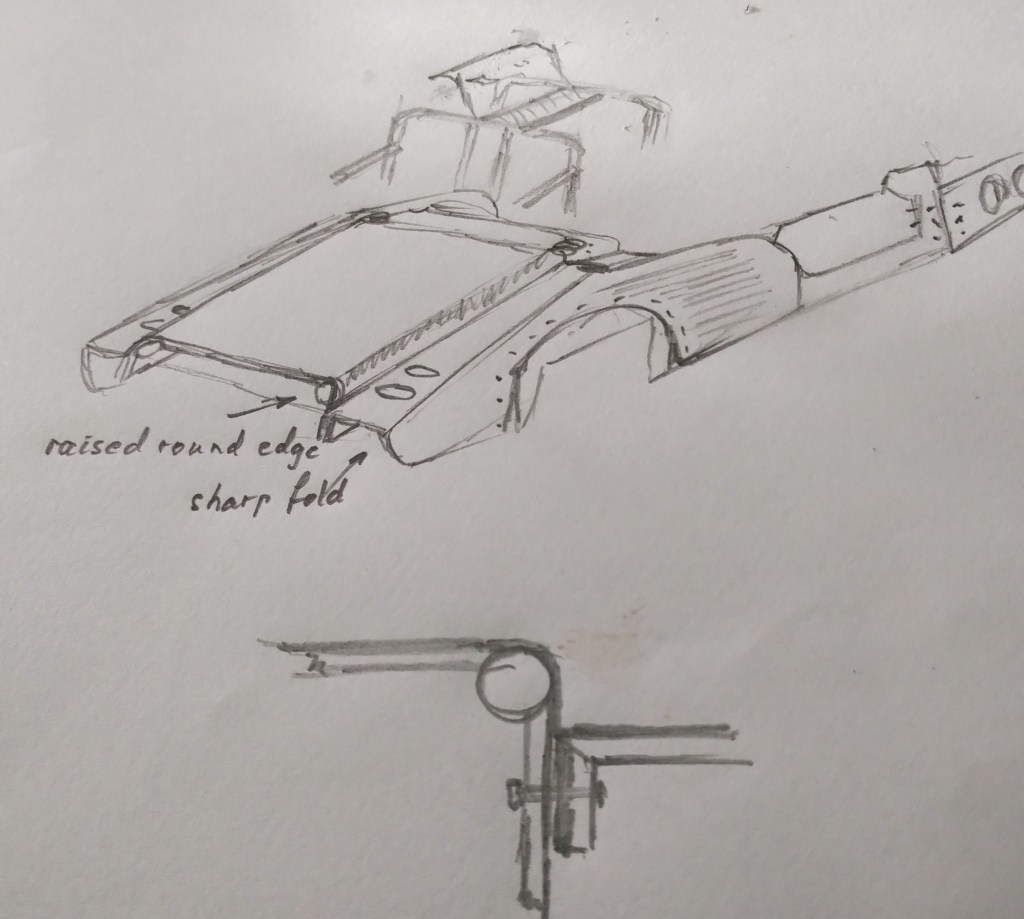

Folds

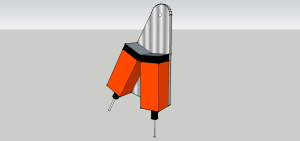

Machine a ‘V’ groove into the wood and the panel can be folded along that line using the aluminium as a hinge. This enables structures to be more than two dimensional and makes seamless direction changes possible. Rounder corners are also possible by wrapping the corner round a tube which is not only attractive but offers a useful conduit for wires, brake lines etc. You’ll see below that all the seams are folded inwards so that when the panels are bolted and glued together the outside finish is clean aluminium.

The fold-round-a-tube concept could be significantly extended. If that tube was part of the steel tubular sub-structure then the added strength of the panels would be significant. For example; the roll bar supports in the rear section would make immensely rigid supports to the rear subframe.

Note that the rounded corner allows room for a press to make the bend accurately and the power allows more choice of cover materials; stiffer ally for example or even stainless steel. Not all the bends have to maximise strength though; a plastic coat is cheaper and allows for interesting printed finishes or even wraps. Interior panels can be leather wrapped even at this early stage in production.

Angles and joins

The basic sports car shape is a box at the back and a tapered front section. This leads to an angled joint, often between separate sections, and this will require an angled plate, or two, to be bolted across the join. As this is usually at the front bulkhead there is scope to make the plates in steel welded to a roll cage/screen frame. If you have to keep it neat, a plate can be fitted right inside the sandwich but obviously it can’t be welded to anything.

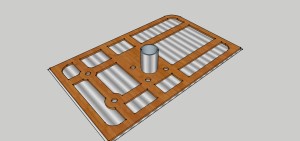

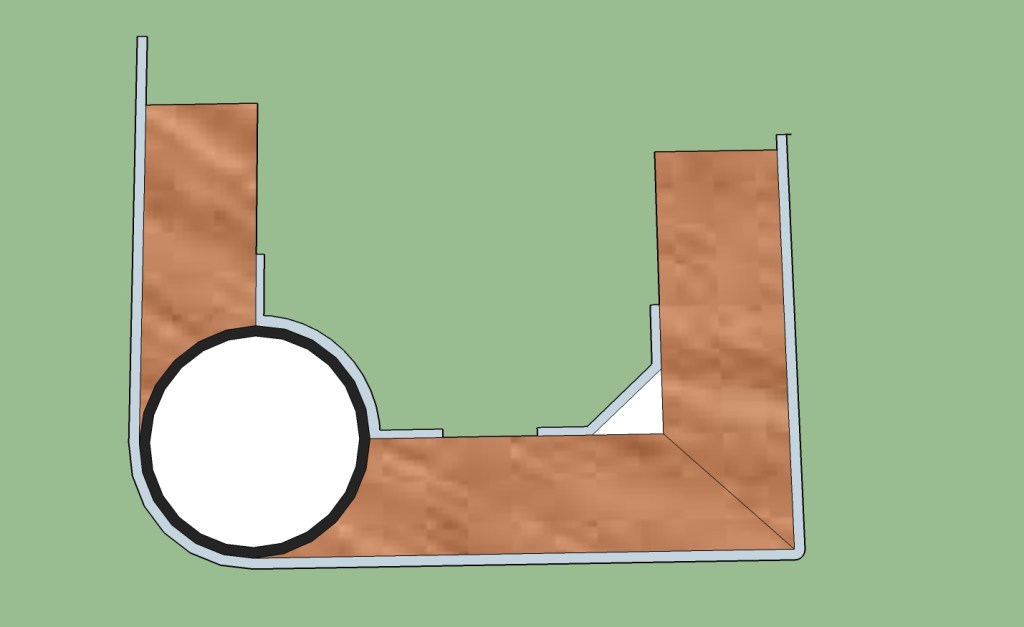

Centre console

This centre console has side panels with appropriate slots inside to take flat slats across. With our trusty router we’d machine all the switch holes etc in the flat and then bend the ally to fit slats to slots. Wood veneer on the outside or ally? Decisions. You can see that an expensive looking centre console is actually just a trivial machining exercise done in a few minutes.

The old ways – but obsolete?

I’d start with Mazda MX5 subframes with all the suspensions diff etc attached. From a production point of view having all these components added to the car with a few buzzes of a nut spinner is a huge plus.

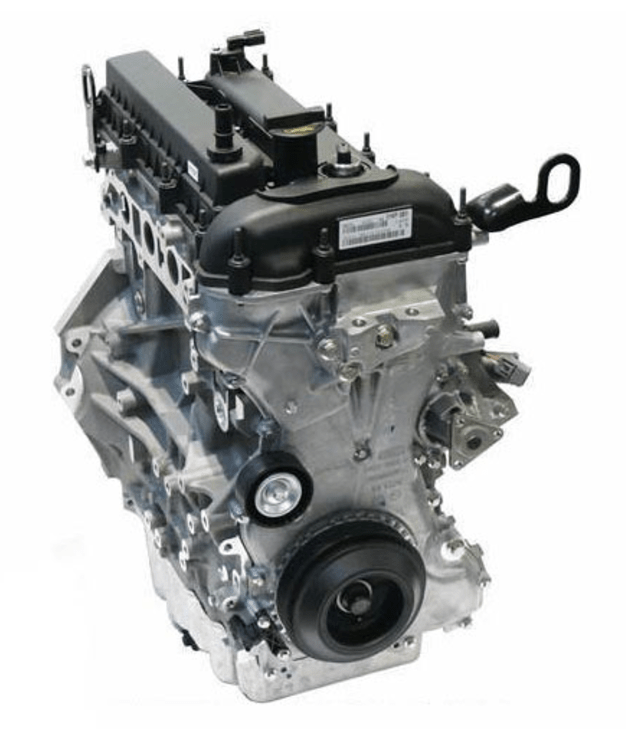

Sticking with Mazda theme a Ford Duratec 2.5 four-cylinder engine is the obvious choice. With VVT this engine goes from a docile traffic crawler to a mad screamer, all at a low price.

Give it the period look with Jenvey Webber 45 DCOE replica throttle bodies which, along with a few mods, will be good for 240bhp.

Apart from being a perfect engine choice, it already sits on the MX5 subframe and bolts up to one of the best manual gearboxes available. There is a good chance that the standard propshaft will fit too. Supercharging (Sprintex) can add well over 100bhp but that’s hardly needed for a light road car – or is it?

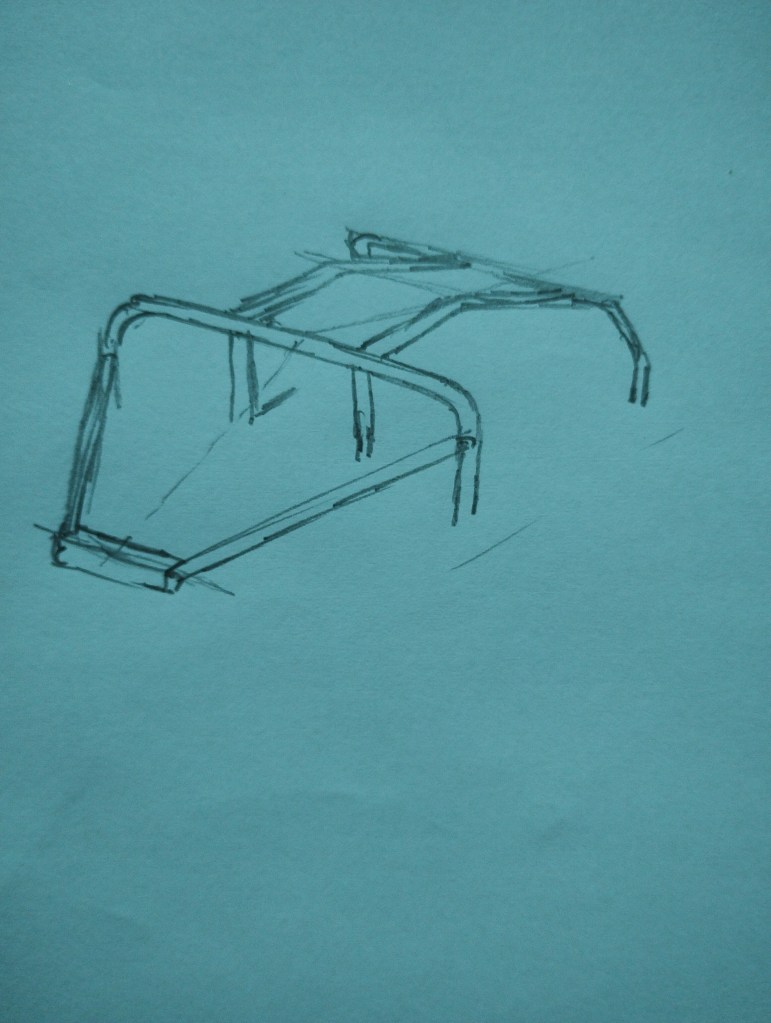

Very fast open top sports cars are downright dangerous. The trouble is you can arrive anywhere very suddenly, and at speed, which catches out other road users and increases the chance of an accident. So, I’d definitely want front and rear roll hoops. I’d go further with connecting tubes down the middle of the car roof to give a radical increase in rigidity. Then I’d do the usual wood and aluminium wrap around the tubes to get a targa top and I’d finish that off with openable and removable polycarbonate roof panels, as sketched previously – instant access for tall drivers at last. Of course, the inside of the roof panel would be machined to take a dash cam, switches and lights – just like a fighter jet then.

Extras – CNC machining already adds huge labour saving value to the panels and this can be taken much further. For example, side panels could have brake lines trapped neatly in the sandwich and the same for wiring too. Pockets for loudspeakers are simple to incorporate; just a few more lines of code for the CNC router. Each panel would become a sub-assembly in its own right and this enables the final assembly of the car to be much quicker and neater.

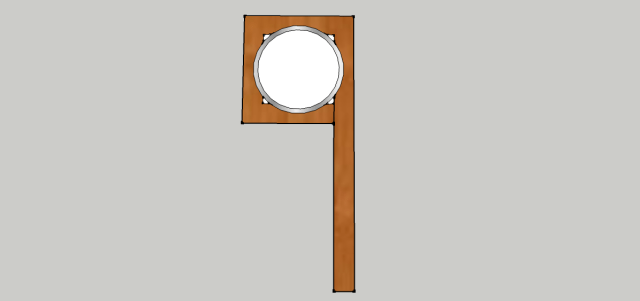

Just by removing wood air ducts can be pre-machined inside the sandwich and this begs the question; could all the components for a heater be incorporated into the dashboard? The external blower just leaves the heat exchanger to fit. Ducts lead to manually adjustable outlets such as the eyeball jobs seen on Cortinas.

You know that brolly hidden in the door idea? A few seconds extra on the CNC so why not?

The laser cutter can make a complex logo in seconds; polycarbonate backing with press fit LED bulbs completes the job. There are no particular restrictions on size so, for example, a huge logo on the back of the car could double as a brake light.

Wings, cowl, seats, heater etc etc – If you are a manufacturer with these on the shelf for an existing car, that would be a good start! I once saw a classic car that was entirely polished aluminium and chrome; might have been an SS Jaguar. Anyway, it looked absolutely fabulous and that look is possible here.

Electric Vehicles

The incredibly light but strong panels described above are perfect for electrification. It’s all about how the loads are fed into the corners via panels that double as chassis members..

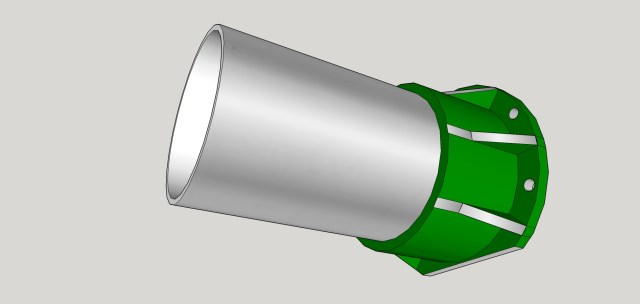

The flat plate concept

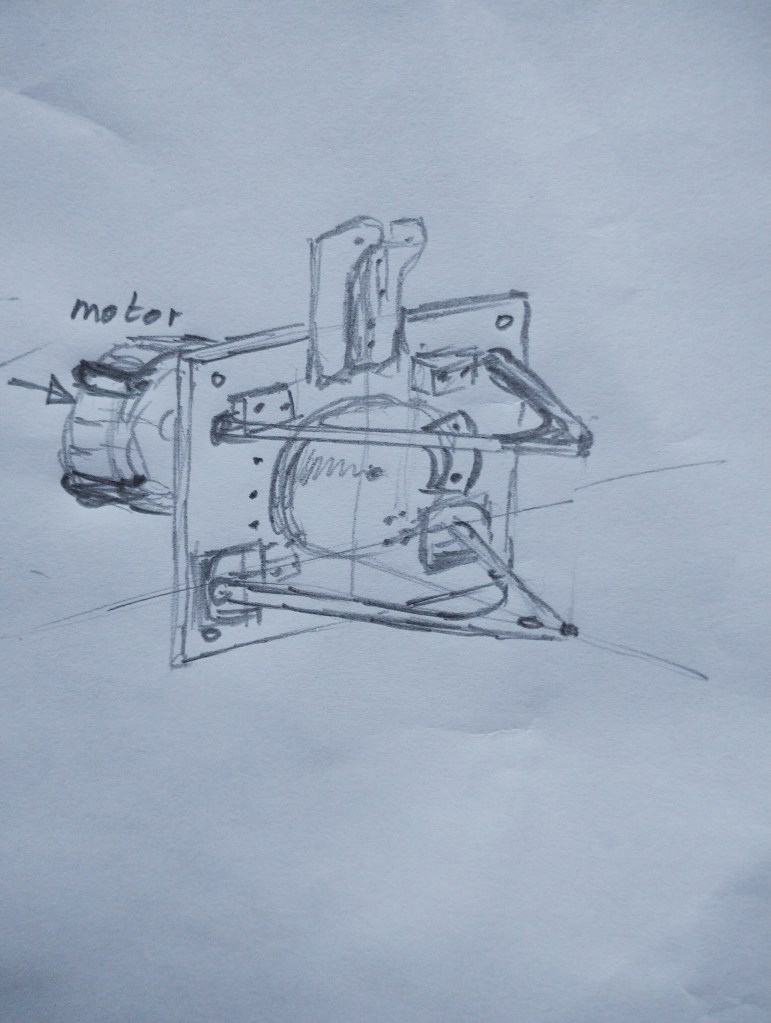

Take any corner of the car and start with a flat plate. On the back of it bolt on an electric motor. On the other side goes a brake disc with its caliper bolted directly to the plate. Unequal length suspension wishbones have mounts bolted to the front and back of the plates and a coilover mounted at the top. That’s about it; all rather neat, simple and cheap, and incorporated beautifully with the body panel which goes between the motor and the plate. Remember, the brake line is already embedded in the body panel so that’s neat too. The motor is brought inboard and protected from the elements. Note the benefits to unsprung weight with inboard brakes. To prevent excess heat from the brake disc being conducted to the motor it will be necessary to space them apart with a coupling in between. The chassis/body panel will also provide some separation and conduct heat away too. Bear in mind that regenerative braking takes away a lot of energy and also that the brake disc can be as big as is needed without having to fit inside a wheel – plenty of space for another caliper if needed.

Talking of cooling; any ally clad panel with Alupex pipe inside (like underfloor heating) would make a cheap oil cooler – not particularly efficient but very neat and dragless too.

Would the plate concept be cheaper to build? Those complex subframes for example – gone. Engine, gearbox, propshaft, diff, all gone. Of course, the neatness of this arrangement easily allows rear-wheel drive or four-wheel drive where 0-60 times under 3 seconds are realistic.

N.B. We still need a deep propshaft tunnel for strength – good place for some batteries. Low polar moment of inertia and all that.

Embedded wires concept – A few motors and battery packs all need heavy wires to connect them. Our flat panels can replace wires with thick aluminium ribbons trapped inside. This could even be like a ring main all round the car; batteries feed in, motors (via inverters) take out, with hardly a wire in sight. Of course, extra strips of aluminium inside body panels all add to the strength; structural wiring! You heard it here first.

Summary – A quickly assembled set of panels make an incredibly light but strong basic body which is so inexpensive it’s hard to see how it would cost more than £2,000, and don’t forget, it does away with a chassis and comes with every mounting hole placed with precision accuracy. Based on an assembly of flat panels it is exceptionally suitable for older style vehicles. Combine all this with the flat plate drive/suspension units and electrification looks like the way ahead.

P.S. Forgive me for trawling through the traditional concepts first but, by contrast, it shows how the electric version is so much more exciting and so delightfully simple that it sweeps away all those old ways of doing things.

CNC routers – If that’s a new world to you I’d recommend CMS from Italy. I’ve used one with six 20hp router motors and twin tables – an awesome beast.

or – here’s one I designed earlier